I hate Kaspi. There, I’ve said it. Just writing the words leaves me waiting for the lightning bolt to strike me down.

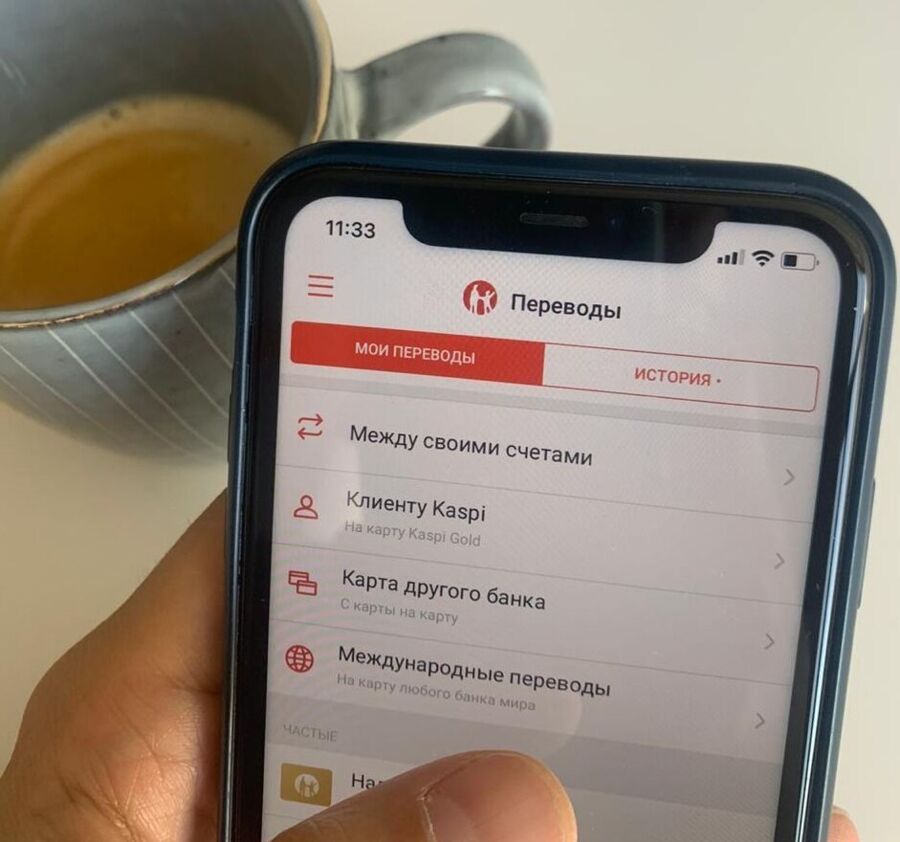

People in Kazakhstan are immensely proud of their home-grown super app, which acts as the main banking, payments, and shopping platform for much of the nation. So proud, in fact, that any utterance against it feels sacrilegious. Like telling an Uzbek that plov isn’t all that good.

The explosive, countrywide adoption of the app since 2017 has simplified life for almost everyone. Indeed, Shyryn Mussina, Managing Director of Marketing at Kazakh Tourism, based in Astana, smiles slightly as I tell her about the angle for my piece over a Zoom call.

“I’m afraid I don’t understand your question,” she says, as I ask her why it’s so difficult for foreigners to make payments in Kazakhstan. “We are one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world when it comes to fintech – possibly the most advanced!”

So let me put it more diplomatically: I hate Kaspi because it’s too good. Kaspi is so good that people wonder why on earth they would bother using any other form of payment. Cash has all but disappeared amongst the young generation and there is a general reluctance, particularly amongst smaller merchants, to route payments via the two American giants, Visa and Mastercard.

For foreigners, this can be an absolute pain. On my last visit here in 2022, in hostels and restaurants, on buses and trains, my attempted card payments were constantly refused. The worst occasion was on a 16-hour train from Almaty to Astana, when I was unable to pay for any food.

Even cash was difficult. I took every opportunity to break up my large denomination notes (up to around $50 in value) in supermarkets, to little effect. So often was I forced to utter the phrase “Keep the change,” to taxi drivers that the visit was somewhat of a diplomatic triumph for Anglo-Kazakh relations. Given the damage that some of my countrymen have done to our two countries’ diplomatic ties over the past three decades, from Norman Foster’s ghastly architectural additions to the Astana skyline to Sacha Baron Cohen vandalizing Kazakhstan’s international reputation for a generation, this was probably much needed.

The experience was so harrowing that it put me off the country; instead, I opted to spend more time visiting Kazakhstan’s low-tech, low-hassle neighbors. But people have assured me that I was exaggerating, and I should give the place another chance. So I’ve decided to head to Kazakhstan’s third largest city, Shymkent, to see if it’s possible to survive there as a foreigner.

Now the first thing you might be asking is, “Why not just download Kaspi?”

Well, I tried. I even got in touch with David Ferguson, Kaspi’s Head of Investor Relations, before the trip. He told me that, sure, I can open an account – however, “new customers are required to be registered in Kazakhstan, have a local tax ID, local mobile phone number, and must be biometrically identified in one of our retail outlets during the account opening process.”

Not the average tourist’s idea of a fun first day.

Still, Mussina and Ferguson both assure me that for any major purchases, I will have no issue paying by card.

As I arrive at Shymkent station on a dank, February morning, I head to the ATM and spend some time pleading with it to dispense the smallest denomination notes possible; it obliges by spitting out some 5000 tenge ($10) bills.

One immediate improvement is that Yandex Go, which was banned from the Apple and Google app stores in 2022 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is now easily available to download. This means I can swerve the gaggle of wise guys at the foot of the station steps, all shouting “Taxi, bratan?” and head over the road to Global Coffee where I can snaffle some Wi-Fi and flag down a ride.

But even when ordering a cappuccino, the rules of the game are made clear: “Cash or Kaspi?” the waitress asks casually.

“Card,” I say firmly.

She frowns slightly, but acquiesces. I take it as a warning shot across the bow.

“Often merchants don’t want to pay the high fees associated with card-based payments,” Ferguson told me, adding that although the firm does provide point-of-sale [PoS] card terminals to its customers free of charge, they tend to be used predominantly by merchants with high transaction volumes.

Having checked into my Airbnb (paid for with Mastercard), I continue playing in easy-mode and go to Shymkent Plaza, the city’s shiny shopping mall, for lunch. Kazakhstan’s multi-vector fast-food diplomacy means it is the only country in the CIS that can boast the whole gamut of American chains, from Burger King to Starbucks. As expected, card payments are no trouble here either.

Then I take things up a notch and quickly discover that card payments are not possible on Shymkent’s buses. Neither do the city’s notoriously impatient bus drivers appreciate being given a 5000 tenge note for a 70 tenge ($0.14) journey.

It’s a similar story at the crumbling art gallery in Abay Park and at a good chunk of roadside kiosks and street food outlets, not to mention the bazaar, one of the most quintessential Central Asian experiences.

Restaurants are a mixed bag. The city’s famous coffee chain, Madlen, is happy to accept any form of payment, but the Uzbek restaurant where I go for dinner is cash or Kaspi.

On my pub crawl that evening, visiting Gentleman’s Pub (not as dodgy as it sounds), 777 bar (exactly as dodgy as it sounds), and Sigma bar, card acceptance is 50/50.

In sum, you can survive in Kazakhstan without Kaspi. The return of Yandex in particular has made the country a much easier place to get around. But it’s still difficult nonetheless. While it’s perhaps a little much to expect every market vendor to be equipped with a card terminal, the disappearance of cash means that tourists and stall holders alike are constantly trying to break up small notes in a quest for change.

Kazakhstan isn’t the only country to operate in this way. China, which pioneered QR-code payments with WeChat Pay and AliPay, used to be similarly kafkaesque to foreign visitors.

Recently however, as Beijing seeks to boost tourist arrivals, these companies have made it simple and painless to add an international card to your WeChat or AliPay wallet. No ID checks, no biometric scanning, no digging into the creditworthiness of your seven ancestors. Just a simple process that takes about thirty seconds and under ten clicks.

I asked Ferguson if Kaspi has any plans to do anything similar.

He explained that, unfortunately, there has to be a full KYC (Know-Your-Customer) process for every new Kaspi client. “We are regulated as a full-service bank, which is a bit different to many fintechs around the world, especially in their early days, which are often regulated in a more ‘lite’ way,” he said.

Ok, so a spoiled western guy can’t go to the bazaar, you might be thinking. What’s the big deal?

And to an extent you’d be right. Western tourists make up a shrinking share of visitors here. The closure of Russian airspace to Western airlines has both raised costs and added time to flights to Kazakhstan. Meanwhile, there has been a boom in tourism from China and India.

According to Mussina, most visitors come on package holidays, where independent expenditure is less necessary. And if someone does insist on traveling under their own steam, why can’t they just go to nice hotels and expensive restaurants which have payment terminals waiting for them?

These are valid points. But who benefits from tourism if visitors are locked out of local payment systems?

The answer is those that can afford to handle lots of transactions and absorb the credit card fees, in other words the large foreign-owned hotels; the Russian taxi company; the American fast-food chains; and the chain stores.

It means that tourism is more likely to be concentrated in cities that are already wealthy, widening an already yawning inequality gap between the rich and poor.

Kaspi is brilliant, it has done wonders for empowering smaller merchants and has pushed other traditional banks to follow suit and offer similar services. Opening digital payments up to foreign tourists strikes me as a way to ensure that the riches reaped from inbound tourism aren’t kept to a select few.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.